by Chiara Pittalis

“There is great value in learning from people on the ground, regardless of their background, if we, as researchers, are open enough to listen.” –Author

As the lead researcher of an innovative project, SURG-Water, I aim to improve access to water for maternal care in rural health facilities in Malawi. My work to strengthen essential services for vulnerable populations– not only in Malawi, but also, Ethiopia, Zambia and Tanzania – dates back several years.

While I have always enjoyed working with rural communities, stepping out of my usual settings in Europe and going beyond my comfort zone, I have realised over time that this demands a unique set of skills. The challenge is not necessarily with the technical aspects of research – there are countless manuals for that! — but with the nontechnical and interpersonal dimensions.

I have observed that, occasionally, some researchers overlook the insights of people from humble backgrounds. This is often due to a mix of stereotyping, lack of exposure, and perhaps a reluctance to go the extra mile to truly understand the lives of other human beings. Too often as researchers we are under immense pressure from our organisations and funders to gather data quickly and efficiently to produce impressive reports, filled with sophisticated analyses and clean results. However, the world outside the safe environment of our offices is not black and white. Reality is far more complex and nuanced, and there is an array of factors that can affect how things are perceived by people on the ground.

Let’s look at the issue SURG-Water aims to address: the fundamental human right of access to water. My interpretation of what access to water entails is likely to be very different from that of a young mother in a small Malawian village where the project works. So, how useful can our reports be if not deeply rooted in the perspectives of those who are meant to benefit from our research? Back to my central point: There is great value in learning from people on the ground, regardless of their background, if we, as researchers, are open enough to listen. The real challenge lies in overcoming pre-conceptions, in crossing over cultural and language barriers to give a voice to the voiceless, and in giving justice to their feedback in our reports. This long and winding road is how I got to know Photovoice Worldwide.

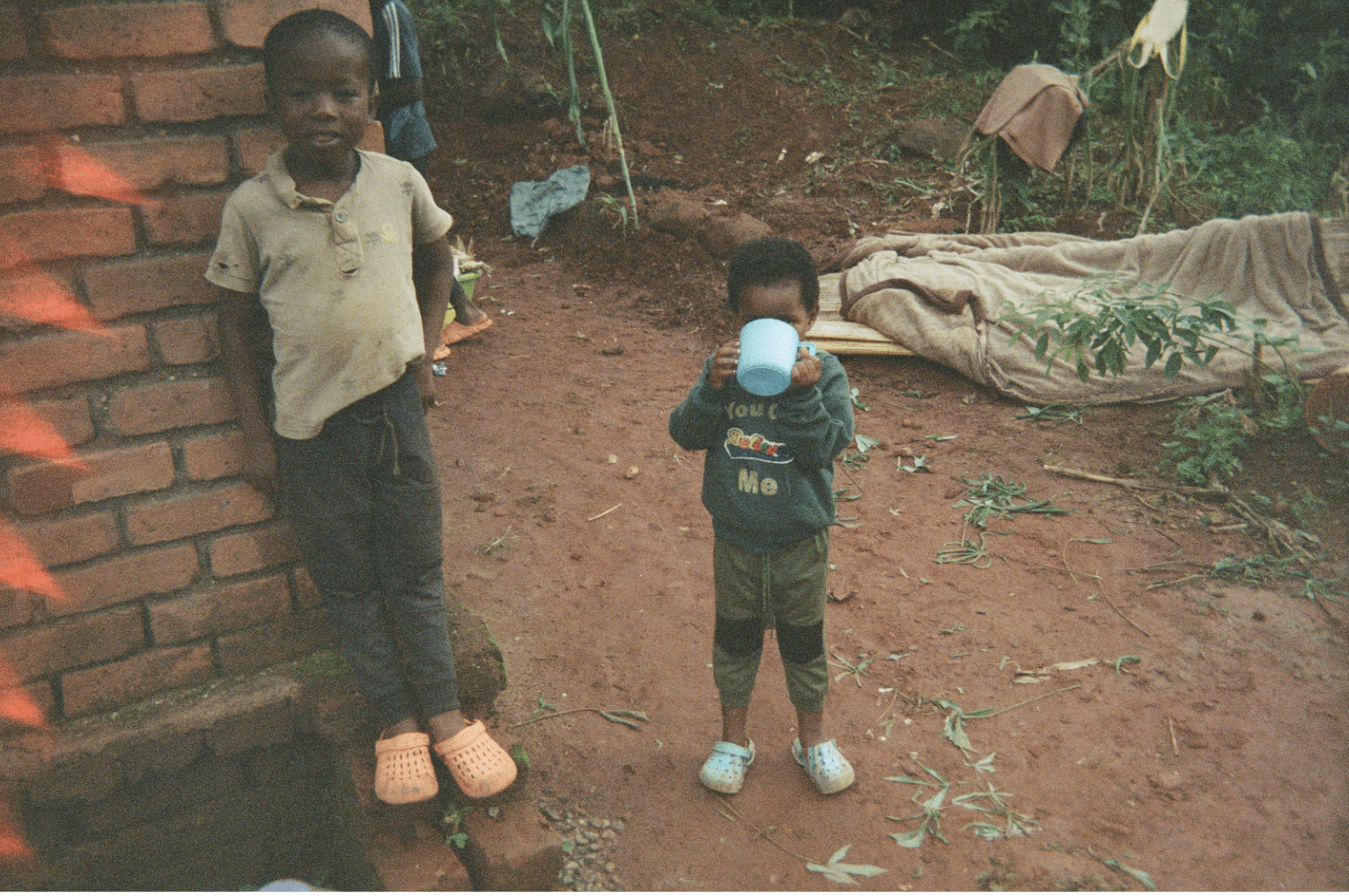

SURG-Water is a participatory research project, and when we started, my team and I were determined to ensure that the perspectives of women in the communities served by our health facilities were duly captured. These communities are very rural, with most people having limited literacy and living modest lives, governed by strong social norms and local traditions. The photovoice method offered a good way to document the struggle of water insecurity as experienced by new mothers and their families despite language and other differences.

We knew what we wanted to capture and which method to use, but how to do so in a way that would be respectful of local culture and put the coresearchers at ease? Despite being an experienced researcher, I firmly believe in self-development and continuous learning. To this end, I enrolled in the Anticolonial photovoice course offered by Photovoice Worldwide, and also signed up for a series of one-on-one mentoring. The aim was to sharpen my skills in cross-cultural and cross-language research, and receive practical advice on how to balance power dynamics between the research team and the coresearchers during the planned photovoice workshops.

A few months have passed since my training — where are we now? I am glad to report that the study has been completed. I must admit it has been an intense and time-consuming process compared to other types of research, but I cannot be thankful enough to Photovoice Worldwide for the guidance received, as this has helped enormously with the hardest part of the task. For instance, I was initially concerned that the coresearchers, who had no prior exposure to research and were unaccustomed to speaking up in unfamiliar settings, might feel intimidated or hesitant. However, the suggestion from Photovoice Worldwide to use ‘gallery walks’ for discussions proved effective in breaking the ice.

Similarly, their advice to remain flexible in our approach by adapting to the needs of the coresearchers helped us navigate social dynamics more effectively. For example, during the initial workshops, local community leaders accompanied the coresearchers. Although this wasn’t originally planned (to minimise potential biases in responses), it was important for them. In rural communities, it is uncommon for individual women to attend events like this unaccompanied, as doing so could be frowned upon by their husbands and others, and viewed with suspicion.

Overall, this has been a very positive experience and a significant learning curve for both myself and the coresearchers. The women came out of their shells to share their perspectives on water issues in their villages, while picking up photography skills along the way. The evidence collected will not only inform our project, but also support other initiatives to tackle water insecurity in rural Malawi.

My message to other researchers considering similar studies is this: Do not be afraid to challenge yourself and explore new approaches; this can greatly enrich your research. At the same time, be well-prepared and humble enough to seek help from others, such as Photovoice Worldwide, because, as Marvin Minsky once said, “You don’t understand anything until you learn it more than one way.”

Note: This initiative was funded by Science Foundation Ireland/Irish Aid and the Royal Irish Academy Charlemont programme.

About the Author

Dr. Chiara Pittalis, based at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dublin, Ireland, is a health systems and services researcher with a multidisciplinary background spanning across the international development sector, academia and consultancy. She is currently lead researcher in a number of projects aiming to strengthen healthcare delivery in low-resource settings, ranging from breast cancer care (Akazi project) to testing innovative solutions to mitigate the impact of climate change on health (SURG-Water project). Her work focuses particularly on participatory approaches to enhance access to care for vulnerable groups, health workforce strengthening, and the role of technology and sustainable innovation in supporting better care delivery.