By Stephanie Lloyd and Laura Lorenz

Are you planning a photovoice project in this midst of these uncertain and stressful times? Were you ready to do a photovoice project and now are re-considering – because your participants can’t go outside, get their project cameras, or meet with you face-to-face? No need to put your project on hold! Photovoice is a highly dynamic and adaptable method. Consider making adjustments that will still provide valid data for interpretation and analysis. Although your ideal photovoice approach may no longer be an option, here are some suggestions for how to adjust your projects during these uncertain times.

Alternatives to photo-taking

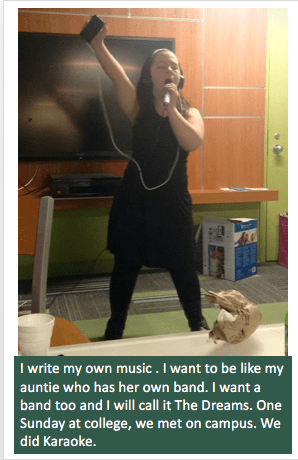

Photovoice photos do not need to be taken for your project specifically. Allow participants to use photos that have been taken previously or by someone else. Right now, while people are being asked to stay at home, encourage participants to look through old photo albums, phone camera rolls, or even on the internet to select photos to discuss with you and others. The important point here is that the photos respond to your project’s prompt or questions, and represent the genuine thoughts, experiences and feelings of your participants.

Participatory visual methods – create art

Because of its many benefits, photovoice may be the ideal method for your study. In light of current events, you can’t give project cameras to your participants, or provide them with photography training or support they may need. Instead, ask your participants to create visuals – drawings, photographs, murals, or videos – to discuss with you (Lorenz and Kolb, 2009). Drawings and other art representations may be helpful to represent feelings and ideas that cannot be captured via photograph during the current times.

Mdantsane Township, Eastern Cape, South Africa, 2001.

Online or virtual focus group sessions

Online or virtual focus groups have increased in popularity as a way to: capture ideas and opinions from a wider demographic, allow greater accessibility for certain populations, and minimize costs and scheduling challenges. Using online software (such as Zoom, GoToMeeting, Join.Me, Google Hangouts, etc.) individuals can participate in an online focus group for free. As long as they are able to access a computer and reliable internet, web conferencing tools allow your participants to talk to each other, see the moderator (and each other if they want), and view a shared picture or document on screen. With online focus groups you have access to the recording and can create a transcript at the end of the conversation, which can support data interpretation and analysis. Make sure you ask participants for permission to record the conversation, whether audio or video!

Online closed groups

When working across global time zones, it might be helpful to use a private Facebook Group, Slack Channel, or other online tool that allows participants to post their photos and respond to prompts at a time that is easiest for them. These channels allow you to work at a different pace as participants access the project “channel” any time they wish, not only in “real time.” With these “channels,” you can specify a time frame (at least a week) for participants to take pictures, share them on the closed group, and post comments. A longer time period allows for more interaction, for example follow-up questions from you (or other group members), and additional photo-taking prompts to narrow down or delve deeper into themes. In their study using Facebook and Photovoice with English teachers, Rubrico and Hashim (2014) concluded that: “The participants found Facebook to be (a) an innovative, fun, and non-threatening venue for engagement, (b) a convenient and broader learning space unbounded by time, and (c) an efficient medium of communication and bonding.”

Jill Nault Connors and Laura Lorenz co-facilitated a photovoice project with individuals living with anxiety disorder that had an online component (Connors et al, 2019). As face-to-face photovoice time was limited, the project used a Slack channel to work together between their face-to-face meetings. Focus group discussions during project time were recorded, and draft captions derived from these conversations were uploaded to Slack along with their related photos. Participants could visit Slack any time to revise their captions, revise their photos, and comment on each other’s work. Connors et al (2019) provides a description of the project’s methods including the online component.

This picture represents the majority of days that I have with anxiety in that there are many days where the steps in front of me look insurmountable. …the bad days with anxiety help me to really appreciative the days where I am stress free. On the good days I am at the top of these steps looking down at the beautiful view.

–Participant, Indiana University, Emergency Medicine, Leveling the Playing Field for Anxiety Disorders, 2018

VoiceThread is another format that groups can use to view each other’s work and use one of five formats to leave comments on selected photos. These formats include microphone, webcam, text, phone, and audio-file upload. The advantage of using VoiceThread is offering participants opportunities to comment, to uploaded photos, and to engage in theme development asynchronously. In her work with young people with IDD exploring experiences and advice related to enrolling in college, Maria Paiewonsky has used photovoice and VoiceThread to enable students throughout Massachusetts to connect with each other and share their experiences. The students developed print and online materials to inspire their peers to consider enrolling in college (Paiewonsky, 2011; Paiewonsky & Lorenz, 2016).

Check out these photovoice project links from Maria Paiewonsky – for both projects participants and facilitator/lead investigator worked remotely using photovoice and other participatory visual methods: Housing First Evaluations: BRIDGES: https://wabridges.weebly.com/ and Mental health and housing: CT MHTG: https://ctmhtghealth.weebly.com/results.html . Be sure to check out the methods tabs for these excellent examples of project websites.

In creating a safe space for young people to participate in photovoice online, Lauren Lichty and colleagues (Lichty et al, 2019) worked with participants over several months to encourage critical thinking. They adopted an online approach to enable students in widely separate locations to participate in a project together, save project resources, and be culturally appropriate. They also incorporated an online evaluation component into their project. They used a WordPress blog and also used private off-blog communicates for additional support. Over the several weeks of the project, these methods allowed participants to reflect deeply on root cause analysis of problems and make sense of their contexts. Lichty et al (2019) provide an excellent description of their online approach.

Things to keep in mind

Overall, the answer is “yes” to doing photovoice remotely – allowing alternatives to photo-taking, creating art, using “real time” meeting software, and using closed online groups – in the correct context. The biggest thing to keep in mind when adapting your photovoice project to a remote or virtual meeting space, is to make sure all participants will have equal access and opportunity. So, when thinking about some of the amazing tech solutions out there, be mindful of the population you are working with and the necessary requirements (e.g. computer, high-speed internet, a camera phone with a data plan) that may not be standard for individuals living in different contexts. Additionally, support participation with a “test run” or provide training on the technology, so that everyone is comfortable prior to the actual data collection time frame. Consider trying the technology in a pilot effort with one or two people to start, and expand as you and your participants gain in confidence. And perhaps most important of all – have fun and enjoy your conversations with participants, however they take place!

Finally, it is important to remember that despite our best efforts, not every photovoice project will result in outcomes we anticipated, whether or not they have a remote component. Participants might need encouragement to take photos and they may or may not remember what they purpose of the photo mission is. They may struggle with the technology options you have decided on. Despite these potential challenges, every photovoice project results in increased awareness of participants’ perceptions, through initial conversations, brainstorming a list of potential photos and even through a discussion of the challenges to complete the work.

Your Turn

Do you have other ideas or questions about conducting photovoice projects remotely? Have you made adjustments to photovoice so you can work remotely? Feel free to reply below or reach out to us at info@photovoiceworldwide.com.

References

Connors, JD, Conley, MJ, & Lorenz, LS. (2019). Use of Photovoice to engage stakeholders in planning for patient-centered outcomes research. Research involvement and engagement, 5, 39-39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-019-0166-y

Lichty, L., Kornbluh, M., Nortensen, J., and Foster-Fishman, P. (2019). Claiming Online Space for Empowering Methods: Taking Photovoice to Scale Online. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice: Promoting Community Practice for Social Benefit. 10(3), September. https://www.gjcpp.org/en/article.php?issue=33&article=201

Lorenz, L.S. and Kolb, B. (2009), Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expectations, 12: 262-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00560.x

Lorenz, LS and Paiewonsky, M. (2015). Chapter 13 “Sharing the results of visual methods research: Participation, Voice, and Empowerment,” Disability and Qualitative Inquiry: Methods for Rethinking an Ableist World (pp 209-220). (Ed. Berger, RJ and Lorenz, LS). London: Ashgate. https://www.routledge.com/Disability-and-Qualitative-Inquiry-Methods-for-Rethinking-an-Ableist-World/Berger-Lorenz/p/book/9781472432896

Nykiforuk, Candace & Vallianatos, Helen & Nieuwendyk, Laura. (2011). Photovoice as a Method for Revealing Community Perceptions of the Built and Social Environment. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.10.1177/160940691101000201.

Paiewonsky, M. 2011. “Hitting the Reset Button on Education: Student Reports on Going to College.” Career Development for Exceptional Individuals 34 (1): 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885728811399277.

Paiewonsky, M., Hanson, T. & Dashzeveg, O., and Western Massachusetts Student Researchers (2017). Put Yourself on the Map: Inclusive Research With and By College Students with Intellectual Disability/Autism. Student Reports: A Think College Transition Brief. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. https://pyotm.weebly.com/

Rubrico, Jessie Grace & Hashim, Fatimah. (2014). Facebook-Photovoice Interface: Empowering non-native pre-service English language teachers. Language Learning and Technology. 18. 16-34. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/44378/1/18_03_action.pdf