Q & A with Photovoice Researcher Julissa Adames-Torres, MSW, LCSW

“It is evident that available formal and informal supports promote hope and adherence to mental health services.”

–Julissa Adames-Torres

In February 2021, Julissa Adames-Torres took the Photovoice Worldwide training “Photovoice 101: Facilitation Basics” led by Stephanie Lloyd, PVWW educator and evaluator. Later that year, Adames-Torres co-facilitated a photovoice project with persons who use the services of the Emma L. Bowen Community Center in Upper Manhattan. Conducted via virtual platform during the COVID-19 pandemic, the participatory project’s photos and captions became the basis for a permanent exhibit, dubbed Café Photovoice, installed at the Bowen Center in March 2022. The exhibit captures the “lived experiences” of participants as they reflected on past, current, and future use of mental health and substance use treatment services, and solutions for service improvement.

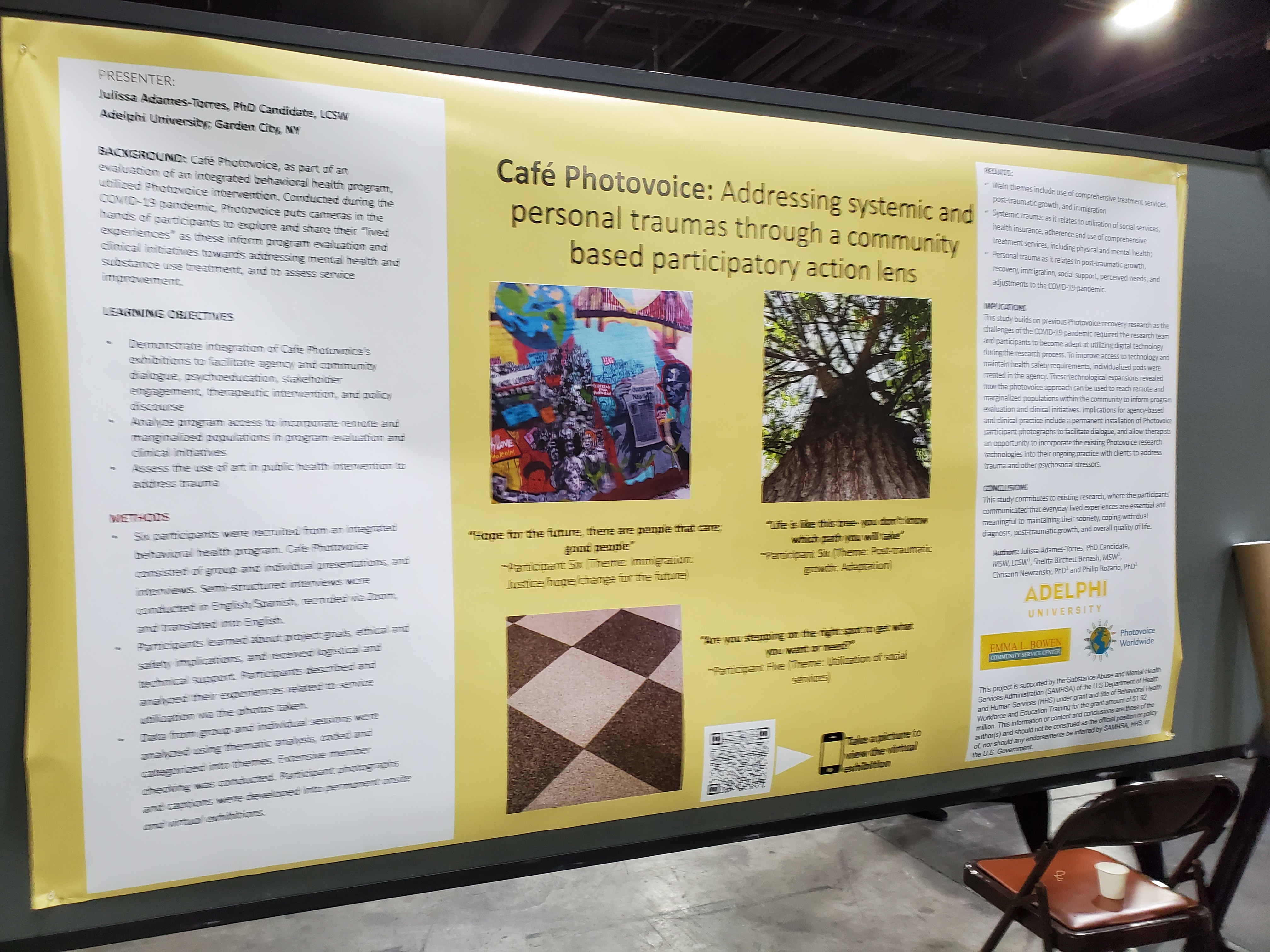

Adames-Torres presented her poster, “Café Photovoice: Addressing systemic and personal traumas through a community-based participatory action lens,” at the November 2023 Annual Meeting and Expo of the American Public Health Association, held in Atlanta, Georgia. While there, Adames-Torres was thrilled to meet the Photovoice Worldwide team in person for the first time.

Café Photovoice Link: https://www.cafephotovoice.org/

PVWW: You have noted that photovoice can inspire hope in people who share their lived experiences using photovoice. How does the process of taking a photo and talking about it with others foster hope, in your experience?

Julissa A-T: We asked our participants to reflect on previous, current, and future solutions to improve their engagement and participation in mental health and substance use services. For many, reflecting on the support received, goals set, and progress made, allowed them to consider “the good” that exists and the “new chapters” to come.

PVWW: Can you give some examples of people expressing feelings of hope during the photovoice project you facilitated?

Julissa A-T: Resilience and hope were very obvious in our photovoice project. For example, one participant captioned a photograph, “Hope for the future; there are people that care, good people.” Another participant wrote a poem titled, “Blue skies,” to reflect on the hope she’s received through hardships.

PVWW: What, if anything, would you replicate or do differently with photovoice in the future to encourage hope among young people in treatment for mental illness?

Digital Photography, ny. 2021

I was just walking down the street in my neighborhood which I usually don’t do and I saw this one. Honestly, it gave me hope for the future. Seeing that there are people out there that care and that are fighting for justice. It just gave me hope for the future that there are actually people out there that care. There’s more good people out there then bad people. Always assume the good in people because there are more good people than bad people.

Julissa A-T: Given our participants’ experiences, and feedback provided throughout ongoing member checking, I would replicate the discussions and research questions that specifically examined the supports available to them. It is evident that available formal and informal supports promote hope and adherence to mental health services.

PVWW: How could photovoice be adapted for use with other vulnerable populations in general during a future pandemic?

Julissa A-T: Providing digital and technological assistance to photovoice participants could help promote photovoice engagement through another pandemic or in efforts to reach vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations. Our ongoing member-checking efforts proved to be a huge asset in following up with participants and also addressing any barriers or supports to engaging in the project.

PVWW: You are a clinical Social Worker. How (if at all) are you bringing photovoice or participatory photography into your clinical practice?

Julissa A-T: As a clinical social worker and lecturer, I have brought photovoice discussions into my practice and classrooms. For example, aligned with cognitive behavioral methods such as behavioral activation, it enables clients who may be experiencing depression and anxiety to engage with photography as a hobby and a clinical tool in therapy. With proper support, it can also help clients work through past traumas and narrative therapy approaches.

PVWW: And how about into your work with students?

Julissa A-T: In teaching research methods and discussing the strengths and limitations of this study, some of my students have expressed ongoing interest in the photovoice methodology for clinical practice and their research papers.

PVWW: Reflecting back on the Facilitation Basics course you took with PVWW, what aspect of the training had the greatest impact on your approach to the project and/or your participants?

Julissa A-T: Stephanie’s course fostered a sense of curiosity by doing. That is, while still in the pandemic and interacting remotely, we practiced sharing photographs and identifying themes while connecting with the other participants in breakout groups. This allowed me to understand the process as a participant, and later as a facilitator.

PVWW: What was it like meeting the Photovoice Worldwide team in person?

Julissa A-T: Meeting the Photovoice Worldwide team in Atlanta was the highlight of the conference! I met Laura and her colleagues and was greeted with joy. I shared that I was presenting our project, and she later visited our poster. It was an honor to hear her feedback about our project as she reflected on the work our participants and research team had done.

PVWW: Any final thoughts?

Julissa A-T: Overall, this project was very close and near to my professional career, as it connected members of the research team and participants alike during an uncertain time.

Café Photovoice Link: https://www.cafephotovoice.org/

Julissa Adames-Torres is a New York State and New Jersey Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) in private practice and a doctoral candidate at Adelphi University. Currently a Lecturer at Lehman College and adjunct faculty at Adelphi University schools of social work, Julissa has vast experience in clinical areas such as depression, anxiety, trauma, immigration, acculturation, and other life transitions. She has worked as a clinical supervisor and administrator to social workers and social work students. Her administrative, clinical, and educational experiences have contributed to her research in cultural humility and predicting factors of mental health utilization among marginalized communities. She teaches courses in human behavior, diversity, oppression, social work practice with individuals and families, group therapy, social work in healthcare, and social work research.