by Mala L. Matacin, Ph.D., University of Hartford, West Hartford, Conn., USA

It is no accident that I am drawn to the photovoice methodology. Its theoretical underpinnings— community-based photography, feminist theory, and empowerment education—are also central to my pedagogical and research sensibilities. However, despite reading countless articles on photovoice, I still didn’t feel I fully understood the process. In order to do it right, I would need professional training. In November 2019 I completed the ‘Talking with Pictures’: Photovoice course, facilitated by educators Laura Lorenz and Stephanie Lloyd through PhotovoiceWorldwide. Their expert training, support, and guidance were invaluable as I ventured into employing the methodology for the first time.

I am a professor of psychology, but love interdisciplinary work. In fall 2020 I began teaching a yearlong honors seminar at my university on the relationship between photography and social change (“Lights, Camera, Activism”). If they didn’t already, I wanted my students to see themselves as agents of change, and photovoice is ideally suited for both personal empowerment and the power to affect policy.

In March 2020, educational institutions all over the world shut down in an effort to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19), scrambling to finish out the academic year in a completely online environment. The beginning of the fall semester was unlike any other in history as we all struggled to rethink the classroom, the campus, and the community. Bali et. al. (2020) argue that the absence of vulnerable populations (e.g., women) in the decision-making process for COVID-19 responses ignore certain and important perspectives. Similarly, university policy decisions were being made using a top-down approach, with little regard to the voices of those we serve—the students. Although not usually seen as a “vulnerable” population, college students have little voice in creating policy regarding their own education. Thus, the aim of our study, “Documenting the College COVID-19 Experience with Photovoice,” was to show what it was like for college students to live and learn this fall semester (2020) amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In this post, rather than report on the study itself, I will reflect on my experience with using photovoice. If you are interested in our findings, please check out our website: https://uhartphotovoice.cargo.site/.

Expect the Unexpected

Even though photovoice is a research methodology, I also found that it can serve as a pedagogical tool that is interactive and meaningful.

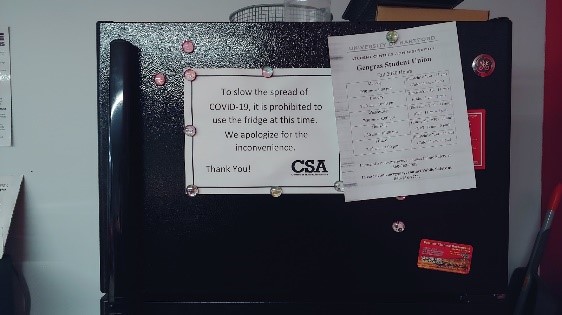

Participatory research is time-consuming, but the students brought to my attention things I never would have known about otherwise. For example, several students were commuters, and their images of isolation were captured in ways that residential students did not share (as evidenced by this photo where refrigeration for meals brought to campus was unavailable).

Another example that shocked me was the increase in trash that was produced on campus. Due to COVID, students were encouraged not to eat in the dining hall, but rather, take food back to their dorms in Styrofoam containers that sometimes overflowed the garbage dumpsters.

One of the big takeaways for me was the level of cognitive flexibility exhibited in the students’ work. No other theme from our project reflected this ability as much as Advocacy (see here for theme descriptions and photos). Students were able to hold two truths: the medical consequences of not wearing masks or social distancing and the larger environmental, racial, social, and political structures that were invariably tied to the pandemic. Many stood in long lines to vote for the first time stating, “the risk was worth the reward.”

Students took photovoice’s goal of engaging with campus policymakers quite seriously, unanimously voting to extend the presentation for two weeks so that they could deliver the best possible exhibit. The list of campus leaders and policymakers they invited are too numerous to name, but included the university’s president and other administrators, public safety, residential life, food services, the COVID Implementation team, and various student services departments. The response was tremendous: approximately 45 guests attended. As with many institutions, the University of Hartford moved all of its classes online after Thanksgiving break, which meant our final exhibit had to take place online. The advantages of an online exhibit were 1) it allowed all photos to be included on the website, and 2) it likely increased the number of people who were able to attend. Policy change takes a long time and certainly cannot be done in a single semester, so our work will continue in the spring to address the two biggest findings in our study: mental health issues and remote learning.

As an educator, one of my top priorities is to create course assignments that connect to what is happening in the world, and certainly, this global coronavirus pandemic is one such event. I found photovoice to be a powerful classroom technique that engaged and empowered students to share their lived experience in courageous ways in order to effect change on campus. In keeping with the photovoice tradition of hearing those whose voices are not typically heard, the next blog relates the experience of two students who took part in this project.

References

Bali S., Dhatt R., Lal A., et al. (2020). Off the back burner: Diverse and gender-inclusive decision-making for COVID-19 response and recovery. BMJ Global Health, 5, 1-3. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002595

Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(3):369-387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309